One of the things that I do to gain experience in physical anthropology and work with people in the field is volunteering in the campus bioarchaeology lab. In the lab, I do skeletal analysis of juvenile individuals, and, as of late, re-assembled teeth and laid them out in order. (Which is a lot harder when they are baby teeth and in four or five different pieces.

In the lab I work under a graduate student who is using the research done in the lab in her Ph.D. dissertation. While we're working, we talk about anthropology-related topics (like grad school), life and how busy we all are, and listen to music while we work on the bones. However, even though it's a casual atmosphere and the person running the lab is only a grad student (opposed to an Associate or Assistant Professor, or someone with tenure who is well-known in the field), working in the lab still requires a form of professionalism in order to demonstrate the level of seriousness that I bring to the field.

I do this by following three rules. First, I go to the lab every day that I am scheduled. The graduate student relies on the undergraduate volunteers to help with the basic research like inventory, epiphyseal union, and metrics in order to speed the research process along. If the undergraduate students don't show up, not only does the graduate student have to do more work, but in addition, it shows that the undergraduate students may not be as serious about the research part of the field as they should be. Plus, the undergraduate students would miss out on experiences in the lab that could help them in the field of physical anthropology as an upperclass undergraduate or a graduate student.

Second, if there is a case where I am unable to go to the lab, I make sure to send the graduate student an email about why I am unable to attend. These cases usually involve a meeting with an advisor or being called into work during the day. In cases where I am required to go to a meeting, I try to go to the lab during the time when the meeting is not held so that I can at least get an hour or two in before I have to leave. Sometimes, like every student, my workload is heavier than normal. If this happens, similar to how I work when I have meetings, I attempt to go to the lab for an hour or two, then leave slightly early in order to do my work. In order to make up for these hours/days, I volunteer to come in and help out if I am particularly free one week or have a class canceled that would otherwise prevent me from being in the lab.

Finally, while I work in the lab, I volunteer for as many "extras" as possible, such working with teeth. Even if I'm not doing any actual analysis of the teeth, I still gain experience putting them together, and over time, I recognize certain things that can help me determine where a certain piece would fit. I can explain this by using a puzzle as an example. When you have a puzzle, if the piece has an edge on one side, you know it's a side piece, while puzzle pieces with two edges are corner pieces. If a tooth has a pointed edge, I know it's a canine. But, if the tooth has a cusp, then it is a molar. In addition to gaining experience and learning what you like and don't like about the lab, volunteering to help out with more advanced stuff demonstrates initiative, which can never hurt in a competitive field like physical anthropology.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

What's That Bone?: Carpals

Carpals.

Also known as the wrist bones. There are eight of them, the hamate, the capitate, the pisiform, the lunate, the trapezoid, the trapezium, the triquestral, and the scaphoid.

Since I work with juveniles, a lot of the times these carpals aren't really defined. And by that I mean they just look like blobs of bone. After a while some of them start to form and it's easier to identify. I always remember which one is the lunate because it looks like a crescent-shaped moon.

The capitate also is an easy one to remember because, when formed, there is a slight representation of a head - thus, it's easy to remember as capitate. (I mostly come up with this reference from the term, "decapitate")

Whenever the wrist bones are formed to the point where I can determine which bone is which, I usually have to use my bone manual in order to tell. You have to pay attention to particular surfaces and match them up to the pictures in the manual - which can be hard if the carpals are in the middle of forming, or don't look exactly like the picture in the book.

Also known as the wrist bones. There are eight of them, the hamate, the capitate, the pisiform, the lunate, the trapezoid, the trapezium, the triquestral, and the scaphoid.

Since I work with juveniles, a lot of the times these carpals aren't really defined. And by that I mean they just look like blobs of bone. After a while some of them start to form and it's easier to identify. I always remember which one is the lunate because it looks like a crescent-shaped moon.

The capitate also is an easy one to remember because, when formed, there is a slight representation of a head - thus, it's easy to remember as capitate. (I mostly come up with this reference from the term, "decapitate")

Whenever the wrist bones are formed to the point where I can determine which bone is which, I usually have to use my bone manual in order to tell. You have to pay attention to particular surfaces and match them up to the pictures in the manual - which can be hard if the carpals are in the middle of forming, or don't look exactly like the picture in the book.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Undergraduate Interview: Valerie Leah

I had the great opportunity of interviewing a fellow physical anthropology undergraduate at Michigan State University this week. Valerie is a super-senior majoring in physical anthropology and criminal justice with a specialization in Peace and Justice studies. During her last year at MSU, she will be doing a research project in the Nubian Bioarchaeology Lab, working with the MSU Undergraduate Anthropology Club, applying to graduate programs, and finally graduating from MSU!

When and how did you become interested in physical anthropology?

I became interested in Anthropology as a Freshman at MSU. During my first semester,

I took classes in Design, anticipating a degree in Interior Design or Studio Art, and

discovered that those programs weren’t right for me. Panicked, I took a bunch of classes

the following semester that just sounded plain fun or interesting. I stumbled upon

Biocultural Evolution, and I was immediately hooked! Quite a turn around, eh?

How have you kept active within the anthropology department as an undergrad?

There are so many opportunities to get involved within the Anthropology Department!

Some of the activities I have been involved in include: being an E-Board member (first as

Events Coordinator and currently as Secretary) of the MSU Undergraduate Anthropology

Club; volunteering and now interning in the MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory;

studying abroad in London, England with the Forensic Anthropology and Human

Identification program; and attending the MSU Campus Archaeology Program Field

School. I try to keep as active as possible!

What was the biggest opportunity you had as an undergraduate studying

anthropology?

That’s a tough one! I’d have to say that it would be the opportunity to be a part of the

MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory’s undergraduate team. There are very few

occasions in which undergraduate students are allowed to learn adult—and very rarely

juvenile—osteology, and the Lab in unique in providing such an environment. It is

invaluable experience! As I finish up my second year in the Lab, I was just offered the

chance to conduct my own research on one of the sections of the collection that has not

yet been studied. I am very excited!

What are certain criteria that you are looking for in terms of grad school? (Profs,

location, prestige, etc.)

Graduate school acceptance, especially at this time, is incredibly competitive, so it is

not wise to be too picky (no matter how tempting it is). Pushing that sentiment aside,

however, some of the key things I am looking at are:

1. Professors: You have to make sure your research interests align and that you

are compatible with them and their program

2. Program Type: Masters or PhD? Anthropology, Forensic Anthropology,

Bioarchaeology, Human Skeletal Biology?

3. FUNDING!: Are there opportunities for funding? If not, what options are

there for students?

4. Location: I’m not too concerned about this point, but if I know that I would

not enjoy the environment I would be living in, perhaps a different program

would be a better choice

What misconceptions did you have about physical anthropology when you first heard

about it? OR What misconceptions do you usually hear from other students who learn that

you are studying physical anthropology?

I get some interesting responses and quite a few misconceptions from students, adults and

family members alike. Here are some of my favorites:

“Isn’t that, like, bugs or something? Gross!”

“How will you find a job digging up dinosaurs?”

“You hate Jesus, don’t you?”

“I hope you have a back-up plan. We aren’t monkeys, you know…”

“Do you have an outfit like Indiana Jones?!”

“*Insert ‘random excitement about Bones’ here*”

What is your favorite part about studying physical anthropology?

Anthropology is all about studying humans, people, and having the chance to give some

sort of identity to someone who is no longer able to tell us about themselves and their

past is an incredibly powerful experience.

When and how did you become interested in physical anthropology?

I became interested in Anthropology as a Freshman at MSU. During my first semester,

I took classes in Design, anticipating a degree in Interior Design or Studio Art, and

discovered that those programs weren’t right for me. Panicked, I took a bunch of classes

the following semester that just sounded plain fun or interesting. I stumbled upon

Biocultural Evolution, and I was immediately hooked! Quite a turn around, eh?

How have you kept active within the anthropology department as an undergrad?

There are so many opportunities to get involved within the Anthropology Department!

Some of the activities I have been involved in include: being an E-Board member (first as

Events Coordinator and currently as Secretary) of the MSU Undergraduate Anthropology

Club; volunteering and now interning in the MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory;

studying abroad in London, England with the Forensic Anthropology and Human

Identification program; and attending the MSU Campus Archaeology Program Field

School. I try to keep as active as possible!

What was the biggest opportunity you had as an undergraduate studying

anthropology?

That’s a tough one! I’d have to say that it would be the opportunity to be a part of the

MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory’s undergraduate team. There are very few

occasions in which undergraduate students are allowed to learn adult—and very rarely

juvenile—osteology, and the Lab in unique in providing such an environment. It is

invaluable experience! As I finish up my second year in the Lab, I was just offered the

chance to conduct my own research on one of the sections of the collection that has not

yet been studied. I am very excited!

What are certain criteria that you are looking for in terms of grad school? (Profs,

location, prestige, etc.)

Graduate school acceptance, especially at this time, is incredibly competitive, so it is

not wise to be too picky (no matter how tempting it is). Pushing that sentiment aside,

however, some of the key things I am looking at are:

1. Professors: You have to make sure your research interests align and that you

are compatible with them and their program

2. Program Type: Masters or PhD? Anthropology, Forensic Anthropology,

Bioarchaeology, Human Skeletal Biology?

3. FUNDING!: Are there opportunities for funding? If not, what options are

there for students?

4. Location: I’m not too concerned about this point, but if I know that I would

not enjoy the environment I would be living in, perhaps a different program

would be a better choice

What misconceptions did you have about physical anthropology when you first heard

about it? OR What misconceptions do you usually hear from other students who learn that

you are studying physical anthropology?

I get some interesting responses and quite a few misconceptions from students, adults and

family members alike. Here are some of my favorites:

“Isn’t that, like, bugs or something? Gross!”

“How will you find a job digging up dinosaurs?”

“You hate Jesus, don’t you?”

“I hope you have a back-up plan. We aren’t monkeys, you know…”

“Do you have an outfit like Indiana Jones?!”

“*Insert ‘random excitement about Bones’ here*”

What is your favorite part about studying physical anthropology?

Anthropology is all about studying humans, people, and having the chance to give some

sort of identity to someone who is no longer able to tell us about themselves and their

past is an incredibly powerful experience.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

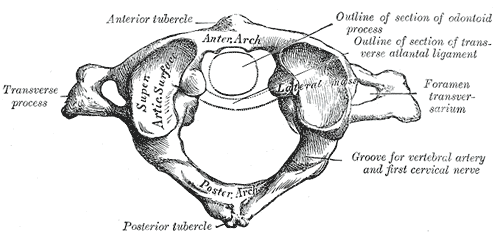

What's That Bone? "Verts"

Verts. Which is the colloquial term from vertebrae.

Just to clarify - vertebra (singular) and vertebrae (plural)

Each person typically has 24 vertebrae (though I have encountered one or two individuals with random extra verts). Technically, the sacrum (the green-colored part of the picture) and the coccyx (the purple) also counts as part of the human vertebral column, but I'm going to stick with the cervical, thoracic, and the lumbar portions of the vertebrae.

There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. A previous instructor once told me of an easy way to remember this. You eat breakfast at 7, lunch at 12, and dinner at 5.

The very first vertebra is called the atlas. One way to remember this is that this vertebra supports the head, similar to how in Greek mythology Atlas holds up the heavens. there is a famous sculpture where he holds up the world.

The second cervical vertebra is called the axis. I remember that it is called this because the axis vertebra is the vert that allows the head to rotate from side to side.

So, while there are a lot of verts, and most of the time they look the same, I have learned some tricks in order to distinguish them from one another. However, I have to say, that most of my knowledge about verts comes from my experience with verts. I love working with verts, even when they're in pieces and you have to put them back together.

While in the lab, I have seen really nice verts, which are wrapped in its specific sections. I've also seen them practically destroyed. When I first started out, it was really hard to pinpoint where all of the verts went, but over time, I've been able to recognize the specific signs.

But that's a lesson that I've learned while working in the lab this year. You can read all of the books, take as many classes, and ace as many exams as possible, but working in the lab really gives you experience that eclipses almost everything else.

Just to clarify - vertebra (singular) and vertebrae (plural)

Each person typically has 24 vertebrae (though I have encountered one or two individuals with random extra verts). Technically, the sacrum (the green-colored part of the picture) and the coccyx (the purple) also counts as part of the human vertebral column, but I'm going to stick with the cervical, thoracic, and the lumbar portions of the vertebrae.

There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. A previous instructor once told me of an easy way to remember this. You eat breakfast at 7, lunch at 12, and dinner at 5.

The very first vertebra is called the atlas. One way to remember this is that this vertebra supports the head, similar to how in Greek mythology Atlas holds up the heavens. there is a famous sculpture where he holds up the world.

The second cervical vertebra is called the axis. I remember that it is called this because the axis vertebra is the vert that allows the head to rotate from side to side.

So, while there are a lot of verts, and most of the time they look the same, I have learned some tricks in order to distinguish them from one another. However, I have to say, that most of my knowledge about verts comes from my experience with verts. I love working with verts, even when they're in pieces and you have to put them back together.

While in the lab, I have seen really nice verts, which are wrapped in its specific sections. I've also seen them practically destroyed. When I first started out, it was really hard to pinpoint where all of the verts went, but over time, I've been able to recognize the specific signs.

But that's a lesson that I've learned while working in the lab this year. You can read all of the books, take as many classes, and ace as many exams as possible, but working in the lab really gives you experience that eclipses almost everything else.

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Faculty Interview: Dr. Wrobel

I had the great opportunity to meet with a MSU anthropology faculty member last week. Dr. Wrobel is an associate professor of anthropology specializing in bioarchaeology. He is also the director of the Caves Branch Archaeological Survey Project in Belize.

When I asked Dr. Wrobel how he became interested in bioarchaeology, he stated that at first he wasn't an anthropology major. In fact, he started in pre-med, but while he was interning at a hospital, he discovered that he didn't really like sick people. He managed to "stumble upon" anthropology, and studied abroad in Mexico. He found archaeology in particular fascinating, and was lucky to work with a professor of biological anthropology as an undergrad.

His favorite experience as an undergraduate was his first archaeological field school in Belize. This experience not only included hands-on archaeology, but also allowed him to be immersed in another culture. He also mentioned that being part of a larger archaeological community including foreign and community scholars was also an incredible experience.

If Dr. Wrobel had the chance to re-study anthropology as an undergraduate, he mentioned that he would like to explore other topics in anthropology and gain a broader picture of the field.

While an undergraduate, Dr. Wrobel had equal passions for both bio-anthropology and archaeology. Because he wasn't sure exactly what he wanted to study, he attempted to gain as many experiences as possible by immersing himself into the field of study and even volunteering with a professor and presenting a paper. Dr. Wrobel's advice for undergraduates in general is, "if you think you might like it, try it out."

However, Dr. Wrobel didn't go directly into graduate school. Before studying at graduate school, Dr. Wrobel worked in contract archaeology in order to gain more experience. By the time he applied to graduate programs, he knew what he wanted to do, including the program and the project. While looking for prospective graduate programs, Dr. Wrobel also made sure that mentors with whom he could work with were also at the university.

Dr. Wrobel mentioned three things when I asked him what were the biggest differences between undergraduate and graduate programs. First, coursework is more specialized, so if you're studying anthropology, all of your classes will be in anthropology or directly related to your specialization. Second, classes are smaller and, thus, more interactive. Third, graduate work also involved professional development, including learning the skills and background to become a professional.

His favorite opportunity during graduate school was the fieldwork. As Dr. Wrobel described fieldwork as the opportunity to do nothing for several months but working on a project that you yourself designed. Furthermore, he mentioned that it can be a little stressful, especially since you make your own decisions.

Finally, Dr. Wrobel offers some advice to undergraduates. He said that undergraduates should immerse themselves into whatever they want to do, whether that would be by touring a lab facility or visiting a site. He also says it's helpful to be inquisitive, and to learn as much as possible.

Thanks, Dr. Wrobel!

When I asked Dr. Wrobel how he became interested in bioarchaeology, he stated that at first he wasn't an anthropology major. In fact, he started in pre-med, but while he was interning at a hospital, he discovered that he didn't really like sick people. He managed to "stumble upon" anthropology, and studied abroad in Mexico. He found archaeology in particular fascinating, and was lucky to work with a professor of biological anthropology as an undergrad.

His favorite experience as an undergraduate was his first archaeological field school in Belize. This experience not only included hands-on archaeology, but also allowed him to be immersed in another culture. He also mentioned that being part of a larger archaeological community including foreign and community scholars was also an incredible experience.

If Dr. Wrobel had the chance to re-study anthropology as an undergraduate, he mentioned that he would like to explore other topics in anthropology and gain a broader picture of the field.

While an undergraduate, Dr. Wrobel had equal passions for both bio-anthropology and archaeology. Because he wasn't sure exactly what he wanted to study, he attempted to gain as many experiences as possible by immersing himself into the field of study and even volunteering with a professor and presenting a paper. Dr. Wrobel's advice for undergraduates in general is, "if you think you might like it, try it out."

However, Dr. Wrobel didn't go directly into graduate school. Before studying at graduate school, Dr. Wrobel worked in contract archaeology in order to gain more experience. By the time he applied to graduate programs, he knew what he wanted to do, including the program and the project. While looking for prospective graduate programs, Dr. Wrobel also made sure that mentors with whom he could work with were also at the university.

Dr. Wrobel mentioned three things when I asked him what were the biggest differences between undergraduate and graduate programs. First, coursework is more specialized, so if you're studying anthropology, all of your classes will be in anthropology or directly related to your specialization. Second, classes are smaller and, thus, more interactive. Third, graduate work also involved professional development, including learning the skills and background to become a professional.

His favorite opportunity during graduate school was the fieldwork. As Dr. Wrobel described fieldwork as the opportunity to do nothing for several months but working on a project that you yourself designed. Furthermore, he mentioned that it can be a little stressful, especially since you make your own decisions.

Finally, Dr. Wrobel offers some advice to undergraduates. He said that undergraduates should immerse themselves into whatever they want to do, whether that would be by touring a lab facility or visiting a site. He also says it's helpful to be inquisitive, and to learn as much as possible.

Thanks, Dr. Wrobel!

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

What's That Bone? The Ilium

I wasn't sure what bone to talk about this week, so my roommate asked me to talk about something in the pelvis girdle. (She stated this while looking through my copy of The Human Bone Manual) And thus I decided to talk about the ilium.

Your pelvis is made up of three bones (not including epiphyses): the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis. In this segment of "What's That Bone?" I will be talking about the ilium, which can be demonstrated by the picture above. If you're still not sure what that bone completely is, it's also your hip bone.

The ilium fuses with the ischium and the pubis to form the acetabulum, which is where your femur (thigh bone) connects to your pelvis.

Because I mostly work with sub-adult skeletons in the lab, I don't get to see many fused pelvic girdles, so I have experience looking at the ilium as separate from the rest of the pelvis. At first I had a little trouble siding them, but then I managed to figure it out after I realized that the auricular surface (a slightly rougher surface than the rest of the bone) fuses with the sacrum (basically your tailbone). So, I tend to double check by sometimes comparing the ilium to my own.

Here's a great picture by the way:

Stay tuned for later in the week, when I will be posting an interview with a bioarchaeologist! And also make sure to check in this Friday, when I talk about the vertebrae on the next segment of "What's That Bone?"!

Your pelvis is made up of three bones (not including epiphyses): the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis. In this segment of "What's That Bone?" I will be talking about the ilium, which can be demonstrated by the picture above. If you're still not sure what that bone completely is, it's also your hip bone.

The ilium fuses with the ischium and the pubis to form the acetabulum, which is where your femur (thigh bone) connects to your pelvis.

Because I mostly work with sub-adult skeletons in the lab, I don't get to see many fused pelvic girdles, so I have experience looking at the ilium as separate from the rest of the pelvis. At first I had a little trouble siding them, but then I managed to figure it out after I realized that the auricular surface (a slightly rougher surface than the rest of the bone) fuses with the sacrum (basically your tailbone). So, I tend to double check by sometimes comparing the ilium to my own.

Here's a great picture by the way:

Stay tuned for later in the week, when I will be posting an interview with a bioarchaeologist! And also make sure to check in this Friday, when I talk about the vertebrae on the next segment of "What's That Bone?"!

Sunday, April 8, 2012

Grad School ... That's After Undergrad

The other day my mom called, and mentioned that in one year I will be (hopefully) graduating from Michigan State University. Which led me to my second thought: What I'm doing afterwards.

I know what I want to do: go to grad school. Now all I have to do is find someone in my field with my interests, or at least, similar interests, look at the programs, take the GRE, apply for schools, get recommendation letters, write personal statements, look into funding, and also maintain all of the things that I currently do (school, organizations, anthropology club, work, eating). It sounds like a lot of work, but hey, others have done it, right?

I'm no expert, but here's what I've been looking for thus far. First, I'm trying to find programs with a physical/biological anthropology program, and at least one professor in the field that does research in bioarchaeology. Second, I look at the professor's recent publications to determine what they do research in, where they do research, other physical anthropologists they have worked with, and what connections they have outside of the university (to other universities, research sites, skeletal collections, etc.). Lastly, I look at the department overall: Does the department have a strong physical anthropology program, or is it only one to two specialists? Does the department have labs pertaining to bio-archaeology?

Other things that are high on my list that others may disagree with includes location. A school in Ohio might have a great program, but for me, where I'm living is almost important. I have to put into perspective that I would most likely be living in this place for 6 - 8 years. I also consider funding. 6 - 8 years is a long time, and in addition to having a nice place to live - location-wise - I also need to recognize that I have school loans currently, and being a professor doesn't exactly pay a lot. There are a lot of options for teaching assistant fellowships, scholarships, grad school fellowships, but I make it a point to look into the funding just to see what is available.

When I apply, I plan on applying to both Masters and Ph.D. programs. I'll apply to a couple that I will consider my safeties, a bunch that I would be an equal contender, and then one or two long shots.

So that's where I am with grad school. I'm kind of going in blind, up to my own devices. I talk to other graduate students, my professors, and my advisors, but when it comes to me, I ultimately have to make the decision. It's crazy to think that in a year I'll (hopefully) be moving somewhere else to study graduate-level physical anthropology.

I know what I want to do: go to grad school. Now all I have to do is find someone in my field with my interests, or at least, similar interests, look at the programs, take the GRE, apply for schools, get recommendation letters, write personal statements, look into funding, and also maintain all of the things that I currently do (school, organizations, anthropology club, work, eating). It sounds like a lot of work, but hey, others have done it, right?

I'm no expert, but here's what I've been looking for thus far. First, I'm trying to find programs with a physical/biological anthropology program, and at least one professor in the field that does research in bioarchaeology. Second, I look at the professor's recent publications to determine what they do research in, where they do research, other physical anthropologists they have worked with, and what connections they have outside of the university (to other universities, research sites, skeletal collections, etc.). Lastly, I look at the department overall: Does the department have a strong physical anthropology program, or is it only one to two specialists? Does the department have labs pertaining to bio-archaeology?

Other things that are high on my list that others may disagree with includes location. A school in Ohio might have a great program, but for me, where I'm living is almost important. I have to put into perspective that I would most likely be living in this place for 6 - 8 years. I also consider funding. 6 - 8 years is a long time, and in addition to having a nice place to live - location-wise - I also need to recognize that I have school loans currently, and being a professor doesn't exactly pay a lot. There are a lot of options for teaching assistant fellowships, scholarships, grad school fellowships, but I make it a point to look into the funding just to see what is available.

When I apply, I plan on applying to both Masters and Ph.D. programs. I'll apply to a couple that I will consider my safeties, a bunch that I would be an equal contender, and then one or two long shots.

So that's where I am with grad school. I'm kind of going in blind, up to my own devices. I talk to other graduate students, my professors, and my advisors, but when it comes to me, I ultimately have to make the decision. It's crazy to think that in a year I'll (hopefully) be moving somewhere else to study graduate-level physical anthropology.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

What's That Bone? The Sphenoid.

This is a sphenoid.

This was the first bone I came across while working in the lab. Now, after several months of consistent analysis, it's a pretty easy bone to pick out. Even when it's broken in several pieces. However, I remember when I first encountered with, myself and the other undergraduates - they were also more experienced, may I add - I was working with, took nearly 30 minutes to finally agree that this was a sphenoid bone.

Now you're probably wondering where this bone - that is oddly shaped like a moth - goes. It is actually part of the skull, and to be more specific, it sits right behind your eye orbits (where your eyes are). I actually found a really good picture that can demonstrate this.

Most often - especially when the skulls are not in complete condition, the sphenoid is broken, but it's unique shape makes it pretty easy to pick out. When the sphenoid is complete, myself - as well as others - usually take a minute to appreciate it, because it really is a pretty bone. It's kind of like in that movie, "The Land Before Time" when Littlefoot finds a tree star, and they all just marvel at it.

So that's the sphenoid. It's a lesser-known bone that I find to be one of the more interesting ones in the human body. Next Friday I will discuss another bone - but you'll have to check in if you want to find out which one it is.

Sunday, March 25, 2012

What I do ...

So, one of the first things that non-anthropology people ask me is: What do you do?

Well, there are two ways that I can answer this question. First, I think I should clarify what I would do as a bioarchaeologist. Basically, I want to study human skeletal remains within an archaeological context. In particular to my interests, I would like to do research within a historical context as well so that I can use written evidence to supplement my research.

By studying human skeletal remains, bioarchaeologists can find out all sorts of things like evidence of nutrition and malnutrition, social standing (in terms of mortuary context), and changes within the population over time, along with others. So basically, when I grow up I want to study the human past by analyzing human skeletal remains and supplementing my research with historical evidence. (It's going to be awesome!)

Now the second way to answer the question is to point out what I do as an undergraduate that can help me achieve this goal. Well, like any person who wants to do research in a competitive field, I can not just go to class. I have to do other stuff as well. I'm part of the undergraduate anthropology club on campus, in which we have guest speakers who give guest lectures about their research. We also do other events like going to the museum on Darwin Day, and information panels with graduate students I also get to meet other anthropologists, and not just physical anthropology students either.

One of the biggest opportunities that I have had as an undergraduate is working in the bioarchaeology lab on campus. As a volunteer, I spend about 7 - 10 hours every week assisting a graduate student with her dissertation research. I lay out skeletons, put them away, do inventory of the bones, epiphyseal union, and measurements of the bones. I have also had the chance to do some dental analysis, but I still do that with the help of a more experienced graduate student.

I also go to brown bags and dissertation proposals and defenses. The information is always really interesting, but going to these types of informational events are also helpful because I can learn what is expected as different stages of the dissertation process. They also help me understand how to present research, which has already come in handy.

So, when it comes down to it, the one thing that I do not do is just go to class. Even if I'm not a professional, I can say with confidence that if you want to be a bioarchaeologist, you can't just go to lecture classes - or even discussion ones - and expect to have enough experience. You have to do things, get involved in the department and network. It sounds like a lot of extra work - and to be honest, it is, but the experience is so worth it.

Plus, if you really want to be a bioarchaeologist, chances are you don't want to sit in 200-person classes and you do want to get out in the field and do stuff. So it all works out anyway.

Well, there are two ways that I can answer this question. First, I think I should clarify what I would do as a bioarchaeologist. Basically, I want to study human skeletal remains within an archaeological context. In particular to my interests, I would like to do research within a historical context as well so that I can use written evidence to supplement my research.

By studying human skeletal remains, bioarchaeologists can find out all sorts of things like evidence of nutrition and malnutrition, social standing (in terms of mortuary context), and changes within the population over time, along with others. So basically, when I grow up I want to study the human past by analyzing human skeletal remains and supplementing my research with historical evidence. (It's going to be awesome!)

Now the second way to answer the question is to point out what I do as an undergraduate that can help me achieve this goal. Well, like any person who wants to do research in a competitive field, I can not just go to class. I have to do other stuff as well. I'm part of the undergraduate anthropology club on campus, in which we have guest speakers who give guest lectures about their research. We also do other events like going to the museum on Darwin Day, and information panels with graduate students I also get to meet other anthropologists, and not just physical anthropology students either.

One of the biggest opportunities that I have had as an undergraduate is working in the bioarchaeology lab on campus. As a volunteer, I spend about 7 - 10 hours every week assisting a graduate student with her dissertation research. I lay out skeletons, put them away, do inventory of the bones, epiphyseal union, and measurements of the bones. I have also had the chance to do some dental analysis, but I still do that with the help of a more experienced graduate student.

I also go to brown bags and dissertation proposals and defenses. The information is always really interesting, but going to these types of informational events are also helpful because I can learn what is expected as different stages of the dissertation process. They also help me understand how to present research, which has already come in handy.

So, when it comes down to it, the one thing that I do not do is just go to class. Even if I'm not a professional, I can say with confidence that if you want to be a bioarchaeologist, you can't just go to lecture classes - or even discussion ones - and expect to have enough experience. You have to do things, get involved in the department and network. It sounds like a lot of extra work - and to be honest, it is, but the experience is so worth it.

Plus, if you really want to be a bioarchaeologist, chances are you don't want to sit in 200-person classes and you do want to get out in the field and do stuff. So it all works out anyway.

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

So it begins ... sort of.

So this is my first post of a blog whose goal is to inform the public about my life as a college student who is super interested in bioarchaeology. As I mentioned in my "Welcome" section (look to the left) - I am not a professional bioarchaeologist. Thus, please don't take this blog as a "how-to" guide on how to become a professional in the field of anthropology. (I still haven't figured that out yet. That's what college advisors and professors are for)

A little about me: I'm a history and anthropology junior at Michigan State University. I was originally just a history major with only a minor in anthropology, but last semester I was given the amazing opportunity to volunteer and help a graduate student in a bioarchaeology lab on campus. I was immediately hooked because it's literally physical evidence of history. I'm a total history nerd, and the fact that I was learning about the past through human remains was super intriguing, I decided to use my extra credits I needed for my degree to get a double major in history and anthropology. When I graduate I'm planning on going to graduate school for physical anthropology with a focus in bioarchaeology so that I can incorporate my history skills into the field.

This website is going to have a lot of different types of information about bioarchaeology, and archaeology in general. There will be pictures, stories about my day, my plans for the future, articles, what I'm learning in class, etc. If you have any questions or comments, please drop me a note! Thanks!

A little about me: I'm a history and anthropology junior at Michigan State University. I was originally just a history major with only a minor in anthropology, but last semester I was given the amazing opportunity to volunteer and help a graduate student in a bioarchaeology lab on campus. I was immediately hooked because it's literally physical evidence of history. I'm a total history nerd, and the fact that I was learning about the past through human remains was super intriguing, I decided to use my extra credits I needed for my degree to get a double major in history and anthropology. When I graduate I'm planning on going to graduate school for physical anthropology with a focus in bioarchaeology so that I can incorporate my history skills into the field.

This website is going to have a lot of different types of information about bioarchaeology, and archaeology in general. There will be pictures, stories about my day, my plans for the future, articles, what I'm learning in class, etc. If you have any questions or comments, please drop me a note! Thanks!