I had the great opportunity of interviewing a fellow physical anthropology undergraduate at Michigan State University this week. Valerie is a super-senior majoring in physical anthropology and criminal justice with a specialization in Peace and Justice studies. During her last year at MSU, she will be doing a research project in the Nubian Bioarchaeology Lab, working with the MSU Undergraduate Anthropology Club, applying to graduate programs, and finally graduating from MSU!

When and how did you become interested in physical anthropology?

I became interested in Anthropology as a Freshman at MSU. During my first semester,

I took classes in Design, anticipating a degree in Interior Design or Studio Art, and

discovered that those programs weren’t right for me. Panicked, I took a bunch of classes

the following semester that just sounded plain fun or interesting. I stumbled upon

Biocultural Evolution, and I was immediately hooked! Quite a turn around, eh?

How have you kept active within the anthropology department as an undergrad?

There are so many opportunities to get involved within the Anthropology Department!

Some of the activities I have been involved in include: being an E-Board member (first as

Events Coordinator and currently as Secretary) of the MSU Undergraduate Anthropology

Club; volunteering and now interning in the MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory;

studying abroad in London, England with the Forensic Anthropology and Human

Identification program; and attending the MSU Campus Archaeology Program Field

School. I try to keep as active as possible!

What was the biggest opportunity you had as an undergraduate studying

anthropology?

That’s a tough one! I’d have to say that it would be the opportunity to be a part of the

MSU Nubian Bioarchaeology Laboratory’s undergraduate team. There are very few

occasions in which undergraduate students are allowed to learn adult—and very rarely

juvenile—osteology, and the Lab in unique in providing such an environment. It is

invaluable experience! As I finish up my second year in the Lab, I was just offered the

chance to conduct my own research on one of the sections of the collection that has not

yet been studied. I am very excited!

What are certain criteria that you are looking for in terms of grad school? (Profs,

location, prestige, etc.)

Graduate school acceptance, especially at this time, is incredibly competitive, so it is

not wise to be too picky (no matter how tempting it is). Pushing that sentiment aside,

however, some of the key things I am looking at are:

1. Professors: You have to make sure your research interests align and that you

are compatible with them and their program

2. Program Type: Masters or PhD? Anthropology, Forensic Anthropology,

Bioarchaeology, Human Skeletal Biology?

3. FUNDING!: Are there opportunities for funding? If not, what options are

there for students?

4. Location: I’m not too concerned about this point, but if I know that I would

not enjoy the environment I would be living in, perhaps a different program

would be a better choice

What misconceptions did you have about physical anthropology when you first heard

about it? OR What misconceptions do you usually hear from other students who learn that

you are studying physical anthropology?

I get some interesting responses and quite a few misconceptions from students, adults and

family members alike. Here are some of my favorites:

“Isn’t that, like, bugs or something? Gross!”

“How will you find a job digging up dinosaurs?”

“You hate Jesus, don’t you?”

“I hope you have a back-up plan. We aren’t monkeys, you know…”

“Do you have an outfit like Indiana Jones?!”

“*Insert ‘random excitement about Bones’ here*”

What is your favorite part about studying physical anthropology?

Anthropology is all about studying humans, people, and having the chance to give some

sort of identity to someone who is no longer able to tell us about themselves and their

past is an incredibly powerful experience.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

What's That Bone? "Verts"

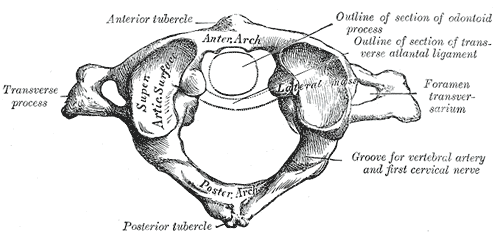

Verts. Which is the colloquial term from vertebrae.

Just to clarify - vertebra (singular) and vertebrae (plural)

Each person typically has 24 vertebrae (though I have encountered one or two individuals with random extra verts). Technically, the sacrum (the green-colored part of the picture) and the coccyx (the purple) also counts as part of the human vertebral column, but I'm going to stick with the cervical, thoracic, and the lumbar portions of the vertebrae.

There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. A previous instructor once told me of an easy way to remember this. You eat breakfast at 7, lunch at 12, and dinner at 5.

The very first vertebra is called the atlas. One way to remember this is that this vertebra supports the head, similar to how in Greek mythology Atlas holds up the heavens. there is a famous sculpture where he holds up the world.

The second cervical vertebra is called the axis. I remember that it is called this because the axis vertebra is the vert that allows the head to rotate from side to side.

So, while there are a lot of verts, and most of the time they look the same, I have learned some tricks in order to distinguish them from one another. However, I have to say, that most of my knowledge about verts comes from my experience with verts. I love working with verts, even when they're in pieces and you have to put them back together.

While in the lab, I have seen really nice verts, which are wrapped in its specific sections. I've also seen them practically destroyed. When I first started out, it was really hard to pinpoint where all of the verts went, but over time, I've been able to recognize the specific signs.

But that's a lesson that I've learned while working in the lab this year. You can read all of the books, take as many classes, and ace as many exams as possible, but working in the lab really gives you experience that eclipses almost everything else.

Just to clarify - vertebra (singular) and vertebrae (plural)

Each person typically has 24 vertebrae (though I have encountered one or two individuals with random extra verts). Technically, the sacrum (the green-colored part of the picture) and the coccyx (the purple) also counts as part of the human vertebral column, but I'm going to stick with the cervical, thoracic, and the lumbar portions of the vertebrae.

There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae. A previous instructor once told me of an easy way to remember this. You eat breakfast at 7, lunch at 12, and dinner at 5.

The very first vertebra is called the atlas. One way to remember this is that this vertebra supports the head, similar to how in Greek mythology Atlas holds up the heavens. there is a famous sculpture where he holds up the world.

The second cervical vertebra is called the axis. I remember that it is called this because the axis vertebra is the vert that allows the head to rotate from side to side.

So, while there are a lot of verts, and most of the time they look the same, I have learned some tricks in order to distinguish them from one another. However, I have to say, that most of my knowledge about verts comes from my experience with verts. I love working with verts, even when they're in pieces and you have to put them back together.

While in the lab, I have seen really nice verts, which are wrapped in its specific sections. I've also seen them practically destroyed. When I first started out, it was really hard to pinpoint where all of the verts went, but over time, I've been able to recognize the specific signs.

But that's a lesson that I've learned while working in the lab this year. You can read all of the books, take as many classes, and ace as many exams as possible, but working in the lab really gives you experience that eclipses almost everything else.

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Faculty Interview: Dr. Wrobel

I had the great opportunity to meet with a MSU anthropology faculty member last week. Dr. Wrobel is an associate professor of anthropology specializing in bioarchaeology. He is also the director of the Caves Branch Archaeological Survey Project in Belize.

When I asked Dr. Wrobel how he became interested in bioarchaeology, he stated that at first he wasn't an anthropology major. In fact, he started in pre-med, but while he was interning at a hospital, he discovered that he didn't really like sick people. He managed to "stumble upon" anthropology, and studied abroad in Mexico. He found archaeology in particular fascinating, and was lucky to work with a professor of biological anthropology as an undergrad.

His favorite experience as an undergraduate was his first archaeological field school in Belize. This experience not only included hands-on archaeology, but also allowed him to be immersed in another culture. He also mentioned that being part of a larger archaeological community including foreign and community scholars was also an incredible experience.

If Dr. Wrobel had the chance to re-study anthropology as an undergraduate, he mentioned that he would like to explore other topics in anthropology and gain a broader picture of the field.

While an undergraduate, Dr. Wrobel had equal passions for both bio-anthropology and archaeology. Because he wasn't sure exactly what he wanted to study, he attempted to gain as many experiences as possible by immersing himself into the field of study and even volunteering with a professor and presenting a paper. Dr. Wrobel's advice for undergraduates in general is, "if you think you might like it, try it out."

However, Dr. Wrobel didn't go directly into graduate school. Before studying at graduate school, Dr. Wrobel worked in contract archaeology in order to gain more experience. By the time he applied to graduate programs, he knew what he wanted to do, including the program and the project. While looking for prospective graduate programs, Dr. Wrobel also made sure that mentors with whom he could work with were also at the university.

Dr. Wrobel mentioned three things when I asked him what were the biggest differences between undergraduate and graduate programs. First, coursework is more specialized, so if you're studying anthropology, all of your classes will be in anthropology or directly related to your specialization. Second, classes are smaller and, thus, more interactive. Third, graduate work also involved professional development, including learning the skills and background to become a professional.

His favorite opportunity during graduate school was the fieldwork. As Dr. Wrobel described fieldwork as the opportunity to do nothing for several months but working on a project that you yourself designed. Furthermore, he mentioned that it can be a little stressful, especially since you make your own decisions.

Finally, Dr. Wrobel offers some advice to undergraduates. He said that undergraduates should immerse themselves into whatever they want to do, whether that would be by touring a lab facility or visiting a site. He also says it's helpful to be inquisitive, and to learn as much as possible.

Thanks, Dr. Wrobel!

When I asked Dr. Wrobel how he became interested in bioarchaeology, he stated that at first he wasn't an anthropology major. In fact, he started in pre-med, but while he was interning at a hospital, he discovered that he didn't really like sick people. He managed to "stumble upon" anthropology, and studied abroad in Mexico. He found archaeology in particular fascinating, and was lucky to work with a professor of biological anthropology as an undergrad.

His favorite experience as an undergraduate was his first archaeological field school in Belize. This experience not only included hands-on archaeology, but also allowed him to be immersed in another culture. He also mentioned that being part of a larger archaeological community including foreign and community scholars was also an incredible experience.

If Dr. Wrobel had the chance to re-study anthropology as an undergraduate, he mentioned that he would like to explore other topics in anthropology and gain a broader picture of the field.

While an undergraduate, Dr. Wrobel had equal passions for both bio-anthropology and archaeology. Because he wasn't sure exactly what he wanted to study, he attempted to gain as many experiences as possible by immersing himself into the field of study and even volunteering with a professor and presenting a paper. Dr. Wrobel's advice for undergraduates in general is, "if you think you might like it, try it out."

However, Dr. Wrobel didn't go directly into graduate school. Before studying at graduate school, Dr. Wrobel worked in contract archaeology in order to gain more experience. By the time he applied to graduate programs, he knew what he wanted to do, including the program and the project. While looking for prospective graduate programs, Dr. Wrobel also made sure that mentors with whom he could work with were also at the university.

Dr. Wrobel mentioned three things when I asked him what were the biggest differences between undergraduate and graduate programs. First, coursework is more specialized, so if you're studying anthropology, all of your classes will be in anthropology or directly related to your specialization. Second, classes are smaller and, thus, more interactive. Third, graduate work also involved professional development, including learning the skills and background to become a professional.

His favorite opportunity during graduate school was the fieldwork. As Dr. Wrobel described fieldwork as the opportunity to do nothing for several months but working on a project that you yourself designed. Furthermore, he mentioned that it can be a little stressful, especially since you make your own decisions.

Finally, Dr. Wrobel offers some advice to undergraduates. He said that undergraduates should immerse themselves into whatever they want to do, whether that would be by touring a lab facility or visiting a site. He also says it's helpful to be inquisitive, and to learn as much as possible.

Thanks, Dr. Wrobel!

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

What's That Bone? The Ilium

I wasn't sure what bone to talk about this week, so my roommate asked me to talk about something in the pelvis girdle. (She stated this while looking through my copy of The Human Bone Manual) And thus I decided to talk about the ilium.

Your pelvis is made up of three bones (not including epiphyses): the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis. In this segment of "What's That Bone?" I will be talking about the ilium, which can be demonstrated by the picture above. If you're still not sure what that bone completely is, it's also your hip bone.

The ilium fuses with the ischium and the pubis to form the acetabulum, which is where your femur (thigh bone) connects to your pelvis.

Because I mostly work with sub-adult skeletons in the lab, I don't get to see many fused pelvic girdles, so I have experience looking at the ilium as separate from the rest of the pelvis. At first I had a little trouble siding them, but then I managed to figure it out after I realized that the auricular surface (a slightly rougher surface than the rest of the bone) fuses with the sacrum (basically your tailbone). So, I tend to double check by sometimes comparing the ilium to my own.

Here's a great picture by the way:

Stay tuned for later in the week, when I will be posting an interview with a bioarchaeologist! And also make sure to check in this Friday, when I talk about the vertebrae on the next segment of "What's That Bone?"!

Your pelvis is made up of three bones (not including epiphyses): the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis. In this segment of "What's That Bone?" I will be talking about the ilium, which can be demonstrated by the picture above. If you're still not sure what that bone completely is, it's also your hip bone.

The ilium fuses with the ischium and the pubis to form the acetabulum, which is where your femur (thigh bone) connects to your pelvis.

Because I mostly work with sub-adult skeletons in the lab, I don't get to see many fused pelvic girdles, so I have experience looking at the ilium as separate from the rest of the pelvis. At first I had a little trouble siding them, but then I managed to figure it out after I realized that the auricular surface (a slightly rougher surface than the rest of the bone) fuses with the sacrum (basically your tailbone). So, I tend to double check by sometimes comparing the ilium to my own.

Here's a great picture by the way:

Stay tuned for later in the week, when I will be posting an interview with a bioarchaeologist! And also make sure to check in this Friday, when I talk about the vertebrae on the next segment of "What's That Bone?"!

Sunday, April 8, 2012

Grad School ... That's After Undergrad

The other day my mom called, and mentioned that in one year I will be (hopefully) graduating from Michigan State University. Which led me to my second thought: What I'm doing afterwards.

I know what I want to do: go to grad school. Now all I have to do is find someone in my field with my interests, or at least, similar interests, look at the programs, take the GRE, apply for schools, get recommendation letters, write personal statements, look into funding, and also maintain all of the things that I currently do (school, organizations, anthropology club, work, eating). It sounds like a lot of work, but hey, others have done it, right?

I'm no expert, but here's what I've been looking for thus far. First, I'm trying to find programs with a physical/biological anthropology program, and at least one professor in the field that does research in bioarchaeology. Second, I look at the professor's recent publications to determine what they do research in, where they do research, other physical anthropologists they have worked with, and what connections they have outside of the university (to other universities, research sites, skeletal collections, etc.). Lastly, I look at the department overall: Does the department have a strong physical anthropology program, or is it only one to two specialists? Does the department have labs pertaining to bio-archaeology?

Other things that are high on my list that others may disagree with includes location. A school in Ohio might have a great program, but for me, where I'm living is almost important. I have to put into perspective that I would most likely be living in this place for 6 - 8 years. I also consider funding. 6 - 8 years is a long time, and in addition to having a nice place to live - location-wise - I also need to recognize that I have school loans currently, and being a professor doesn't exactly pay a lot. There are a lot of options for teaching assistant fellowships, scholarships, grad school fellowships, but I make it a point to look into the funding just to see what is available.

When I apply, I plan on applying to both Masters and Ph.D. programs. I'll apply to a couple that I will consider my safeties, a bunch that I would be an equal contender, and then one or two long shots.

So that's where I am with grad school. I'm kind of going in blind, up to my own devices. I talk to other graduate students, my professors, and my advisors, but when it comes to me, I ultimately have to make the decision. It's crazy to think that in a year I'll (hopefully) be moving somewhere else to study graduate-level physical anthropology.

I know what I want to do: go to grad school. Now all I have to do is find someone in my field with my interests, or at least, similar interests, look at the programs, take the GRE, apply for schools, get recommendation letters, write personal statements, look into funding, and also maintain all of the things that I currently do (school, organizations, anthropology club, work, eating). It sounds like a lot of work, but hey, others have done it, right?

I'm no expert, but here's what I've been looking for thus far. First, I'm trying to find programs with a physical/biological anthropology program, and at least one professor in the field that does research in bioarchaeology. Second, I look at the professor's recent publications to determine what they do research in, where they do research, other physical anthropologists they have worked with, and what connections they have outside of the university (to other universities, research sites, skeletal collections, etc.). Lastly, I look at the department overall: Does the department have a strong physical anthropology program, or is it only one to two specialists? Does the department have labs pertaining to bio-archaeology?

Other things that are high on my list that others may disagree with includes location. A school in Ohio might have a great program, but for me, where I'm living is almost important. I have to put into perspective that I would most likely be living in this place for 6 - 8 years. I also consider funding. 6 - 8 years is a long time, and in addition to having a nice place to live - location-wise - I also need to recognize that I have school loans currently, and being a professor doesn't exactly pay a lot. There are a lot of options for teaching assistant fellowships, scholarships, grad school fellowships, but I make it a point to look into the funding just to see what is available.

When I apply, I plan on applying to both Masters and Ph.D. programs. I'll apply to a couple that I will consider my safeties, a bunch that I would be an equal contender, and then one or two long shots.

So that's where I am with grad school. I'm kind of going in blind, up to my own devices. I talk to other graduate students, my professors, and my advisors, but when it comes to me, I ultimately have to make the decision. It's crazy to think that in a year I'll (hopefully) be moving somewhere else to study graduate-level physical anthropology.